Sunday, May 13, 2012

The Great Schism

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

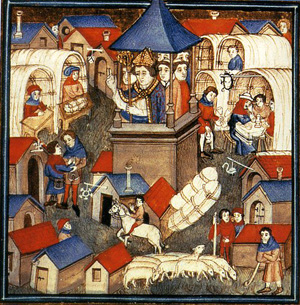

Everyday Life in Medieval Europe

Monday, April 2, 2012

Medieval Religious Practices and Institutions

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Universals

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

Universals?

Monday, March 12, 2012

Universals Controversy

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Early Disputes of Christian Doctrine

2 Great points of Christian dispute: Filioque & Papal Supremacy

Nicene Creed

-the most widely used Christian liturgy (Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Angelican, major Protestant Churches)

First Council of Nicaea /FILIOQUE

-325, modern day Turkey

-established the first uniform Christian doctrine

-the first ecumenical council, about 300 bishops in attendance

-called by Constantine (the emperor who tolerated and later converted to Christianity) who wanted a unified church; an important instance of the church being given authority by the state

-the controversy of Filioque: is the Son of the Father divine?

-Arius and his follower (Arians) claimed that the Son was created by the Father, and therefore not equal in nature

-the consensus of the council was that the Trinity is united: the Father and Son are of the same substance & co-eternal

-Arius exiled

-the council was far from definitive however, as Arius’s views were not suppressed (the two emperors who followed Constantine were Arians)

-around 360 issues arose when people realized that the nature of the Holy Spirit was still a mystery

Theodosius/ First Council of Constantinople (381)

-last emperor to rule both the eastern and western empires (Byzantine & Roman empires), died 395

-named Catholicism the state religion

-called the Council to repair the schism between the East and West

-Differences between East and West : linguistic and cultural (Latin in West, Greek in east=translation nightmares)

-the East by now had gained greater influence, 3 presiding bishops were Eastern; the bishop of Constantinople was second only to the bishop of Rome

-Con. was firmly Arian; men had to decide the nature of the Holy Spirit; the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are equal, though the HS ‘proceeded’ from the Father, while the Son was ‘begotten’ of him

-there were a number of ‘heretical’ sects of Christianity, though most of them were relatively insignificant and died off due to lack of followers or oppression

Papal Supremacy

-what does it mean to be the Bishop of Rome? Is he the ultimate authority or merely the ‘first among equals’?

-the West naturally wanted to give greater authority to Rome than the East, this became a major source of conflict

-eventually the West demanded to be recognized as supreme, the East refused, and the Great Schism followed

The Great Schism

-differences of Doctrine, Theology, Geography, Politics, Language, Culture

-the other language is outlawed

-in 1054 both Bishops try to excommunicate each other, the Church split

-early 16th century Luther and the 95 Thesis mark the beginning of Western Protestantism

Sunday, February 26, 2012

The Islamic Golden Age

- The Islamic Golden Age was an era of blossoming intellectual and cultural achievement in science, philosophy, engineering and other fields within Islamic Civilization from the mid-8th century to the mid-13th century. The empire was ruled by the Abassid Caliphate. The Age was built upon the successful expansion of the Arab empire into North Africa, parts of Europe, and South and Southeast Asia. The successful expansion was attributed to reasons related to the strength of the armies, the use of common language, and the fair treatment of conquered peoples. These factors allowed for a free exchange and blending of multiple traditions from different regions.

- Ceramics, glass, metalwork, textiles, illuminated manuscripts, woodwork, painting, and calligraphy flourished.

- Scholars took important medical knowledge from Rome, Persia, and especially Greece and then made their own advancements.

- Islamic scholars translated philosophical literature from many cultures including China, India, and Ancient Greece.

- In early Islamic philosophy, two main currents may be distinguished. The first is Kalam, that mainly dealt with Islamic theological questions, and the other is Falsafa, that was founded on interpretations of Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism. There were attempts by later philosopher-theologians at harmonizing both trends, notably by Avicenna and Averroes.

- The decline of the Islamic Golden Age was the result of several factors, including the end of the Abassid Caliphate, which decentralized power.

- Religious groups splintered and fundamentalism was on the rise. The appeal by some theologians including Al-Ghazali turned the tide toward orthodoxy, declaring reason and its entire works to be bankrupt. They declared that experience and reason that grew out of it were not to be trusted. As a result, free scientific investigation and philosophical and religious toleration were phenomena of the past. Schools limited their teaching to theology and scientific progress came to a halt.

- The European Crusades (1097-1291) assailed Islam militarily from the West and the Mongols invaded from the East. The Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258 is widely considered the end of the Golden Age as the Islamic Empire never recovered. Trade routes became unsafe. Urban life broke down. Individual communities drew in upon themselves in feudal isolation. Science and philosophy survived for a while in scattered pockets, but the Golden Age of Islam was at an end.

Sources

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_Golden_Age

http://robtshepherd.tripod.com/islamic.html

http://regentsprep.org/Regents/global/themes/goldenages/islam.cfm

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

The Dark Ages

Friday, February 3, 2012

Nova - The Illusion of Time (documentary)

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Augustine: Learning

Augustine: Truth

Belief without understanding

I would like to examine not necessarily a passage, but more of an overarching state of mind of the people of Augustine's time. The people of this era had unshaken faith in the existence of god , even though they did not understand certain aspects of their own faith. The work as whole demonstrates this . Augustine and Evodius both do not fully understand free will, how it should be used, or if it was given by god, yet they both believe without fully understanding. The second section of the work has several quotations that demonstrate this perfectly. The stretch from the bottom of the second paragraph that begins with " yet if it is certain that god gave free will, however it was given, we must acknowledge that.............." and ends at the top of the next page with " A. At least you are certain that god exists- E . I accept even this by faith and not by reason" is this view in a nutshell. This is in striking contrast to the types of thinkers in the age of reason who worked tirelessly to find " proof" for the existence of god. The Enlightenment sought out a base or reasoning behind things in nature, and many saw god as no different. Even if God was a higher being than other things in nature, it still must have some logic behind it. The church ruled these times with an iron fist. To speak out against the church or to question it's dogmas was punishable by death. Many great thinkers like Galileo were seen as enemies of the church, and forced to recant or be put to death. I am not surprised that the masses, almost all of whom were poorly educated, believed with blind faith, but I am surprised that even intelligent philosophers were in this frame of mind as well.

What I find most interesting about this concept is the special place it is given by the human mind. People almost always want sound reasons why they are expected to believe something. " I'll believe it when I see it" or " Prove it" are common phrases . However, religion is given the free pass. People see past all of the evidence, and just have faith that a supreme being exists. It has always interested me . Many have searched for the reason why, perhaps we are all just afraid of death, perhaps we do not like to take the blame for things that happen. Overall I chose this because it demonstrates just how powerful the church of this time was. There was zero doubt in the minds of even the most educated ( or maybe they were just too afraid to say it )

Augustine: Happiness

I was interested in Augustine’s discussion of happiness in On Free Choice of the Will. I will examine two statements in particular that Augustine made in relation to happiness.

1. “The happy life…is man’s proper and primary good” (81-82). Frankly, I was surprised to see an early Christian theologian place a great emphasis on happiness. Christianity is founded on martyrdom, and holds the next life to be much more important than this one. Shortly before Augustine’s time, Christians were regularly persecuted and sometimes thrown to lions; their lives were anything buy happy. A sign of a good Christian was praising Jesus/God as one was about to be murdered for believing in them, having faith that although this life was terrible, the faithful would be rewarded in the next. Augustine, however, states that a happy life is man’s primary good, a notion that may have seemed alien to those whom had been martyred. Now of course (according to Augustine) one cannot live a happy life if one is concerned only with this world, wisdom and happiness come from being in touch with something greater (like numbers!), however happiness is now no longer confined only to the afterlife. I imagine that this shift in outlook was made possible by Constantine’s conversion to Christianity.

2. “we all wish to be happy, so it is agreed that we all wish to be wise, since on one without wisdom is happy” (58). I think this statement is flat-out incorrect. People may wish to be happy, but I don’t believe that wisdom is seen as being a necessary part of that, or that the unwise are necessarily unhappy (see Voltaire’s short story “The Good Brahmin”). Though I don’t like this phrase at all, there is a significant amount of truth to ‘Ignorance is Bliss’. I think that Augustine’s assumption that everyone seeks to be wise is a case of him believing that people want to be what they should be (or rather, what he thinks they should be). Augustine’s knowledge of the Forms has brought him happiness, but it is a leap to claim that people are looking for something they haven’t discovered. I realize that Augustine’s work is dogmatic in nature (‘I believe so that I may understand’), but to claim that everyone seeks to be wise is a very hard statement to justify empirically; and, in the spirit of Plato, Augustine does not attempt to.